If you’re unconvinced that unemployed workers are an adequate measure of available labor, we can extend that definition to include workers who are currently employed in those roles. Recall that the unemployed plus the employed constitute the labor force. Here, we use the labor force as a measure of labor availability for STEM, CMS and non-STEM workers.

This time, the number of job openings is in the numerator and is expressed as a share of the labor force. This is often referred to as the job vacancy rate. Here, a bigger number would indicate a tighter labor market, showing that there are a larger number of job openings relative to the ability of the labor force to fill them. A smaller job vacancy rate would indicate the opposite.

We still see a similar story, though less pronounced: there is a larger number of job openings relative to available labor to fill those roles in STEM and CMS, compared with fields outside of STEM. The difference between this chart and the prior one likely has to do with a more rapidly declining unemployment rate and higher employment growth in STEM and CMS—both positive signs.

Conclusion

Wage growth for STEM and CMS workers with at least a bachelor’s degree has been more robust during the last twelve years than it has been for workers outside of these fields. Not only did wages grow at the median for these fields while wages in all other professions fell substantially, that growth also reached workers with a broader set of income levels.

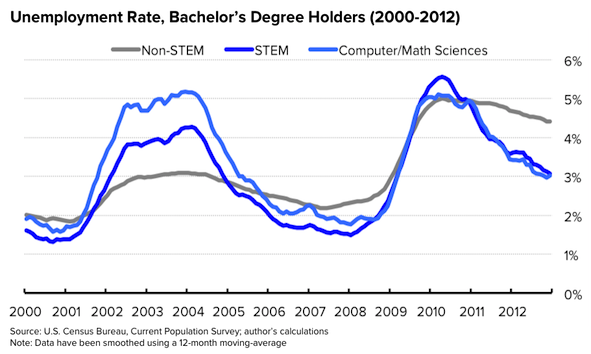

Looking at other measures, available labor to meet job openings has been scarcer for the STEM and CMS fields, employment growth has been more robust, and unemployment has fallen to lower levels. The evidence is more mixed when it comes to unemployment, but overall the consistency across measures and the magnitude of differences point to tighter labor markets in these fields.

In fact, according to performance thresholds to assess labor market tightness outlined in a comprehensive review of the literature published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the CMS labor market is tight on each of three metrics (employment, wages, and unemployment). STEM is tight on two of three (wages and unemployment) and goes halfway on the third (employment). The BLS report doesn’t provide threshold criteria for job vacancies because these data weren’t available at that time.

This highlights a few important points worth making. Firstly, providing definitive evidence of the existence or nonexistence of a labor shortage in any profession is difficult, both because what constitutes a shortage can be broad based and because the appropriate data can be elusive. It’s irresponsible for researchers to claim there is an oversupply of STEM workers because of one metric taken outside of its proper context.

To be clear, the approach here does not claim that there is a shortage of workers in STEM and CMS fields. Instead, it shows that these labor markets are tighter than others based on a broad set of measures. At minimum, it is a clear rejection of the notion that we have too many high-tech workers in the United States—an argument that not only fails on evidence, but common sense as well.

Secondly, and perhaps most importantly, the argument about whether there is or is not a true shortage of STEM workers misses the entire point. Recent research has shown that foreign-born STEM workers increase employment and wage opportunities for high-skilled native-born American workers (STEM and non-STEM). In other words, these workers are complementary to, not substitutes for, one another. Foreign-born STEM workers are important contributors to productivity gains, which fuel economic growth and national prosperity. And because these workers tend to be employed in sectors of the economy that compete globally, if the United States doesn’t capture the talent and therefore growth, someone else will.

Let’s get our facts straight, and in context, as we move forward with immigration reform. Sure, foreign worker programs like the H-1B visa have a number of problems and need rethinking. So does our education system. But let’s fix those, not shut our doors to high-skilled foreign workers based on poor economics. That would be throwing the baby out with the bathwater, and in the process, shooting ourselves in the foot.