The Bureau of Economic Analysis released a first revision of GDP numbers for the third quarter today, with growth coming in at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 3.9 percent. If the number holds, it and the second quarter will mark the strongest consecutive quarters of growth since 2003. Also out today, Alan Blinder of Princeton University has a piece in the Wall Street Journal, where he argues that not enough attention is being paid to the “dismal” productivity growth occurring the last four years—in part because of the difficulty in forecasting this measure. Given today’s data release, the Blinder op-ed, the technology and employment debate, a growing discussion about a world of persistently slow growth, and some chatter today on Twitter, I became curious about what role ICTs might be playing in the shorter-term—in the economic recovery of the last few years to be more precise.

Even piecemeal immigration reform could boost the U.S. economy

This was originally posted on Fortune

(with Robert Litan)

With President Obama expected to make a statement about immigration tonight, Washington is gearing-up for a fight over the President’s seeming willingness to exercise his executive authority to prevent the deportation of primarily low-skilled immigrants. While that’s worth watching, the more important economic picture risks getting lost: the impact that immigrants can bring to the American economy in the long-term. It’s the immigration discussion we ought to be having, and if the rumors are correct as of this writing, it’s the one the President will at least partially extend in the executive action that he will outline.

High-skilled immigrants are good for America, and we should encourage more of them to come here given recent trends in entrepreneurship, where more firms are dying than being created every year. But high-skilled immigrants could help turn that trend around -- they are twice as likely to start businesses as native-born Americans. This is especially true in high-tech sectors, where immigrants are not only more likely to start firms, but also to patent new technological discoveries. Giving green cards to foreign students completing STEM degrees at U.S. universities, and to many more immigrant entrepreneurs, would increase income and employment opportunities for American workers across the board.

We have recently published new evidence at the Brookings Institution that supports the link between immigration reform and economic growth. Our research brings a new perspective -- the importance of entrepreneurs -- to an older idea: the link between greater population growth and economic expansion.

This connection was at the heart of concerns expressed by Harvard economist Alvin Hansen in his address, “Economic Progress and Declining Population Growth," before the American Economic Association in 1938. Hansen worried that what he saw as falling rates of population growth and technological advance portended a slump in investment, which would lead to persistently low employment and income growth. Hansen’s forecast never came true, thanks to post-war booms in innovation and fertility rates.

Three-quarters of a century later, another Harvard economist, Larry Summers, has updated Hansen’s concept of “secular stagnation” to describe post-recession slow growth across much of North America and Europe. In the year since Summers first made his remarks, economists have been debating whether and to what extent his thesis will hold in the future.

Much less publicized is another debate that concerns the current and future state of U.S. economic growth—that of a pervasive decline in the rate of firm formation and economic dynamism. We and others have documented this decline in a broad range of sectors and regions throughout the United States during the last few decades—a decline that even reached the high-tech sector and so-called high-growth firms, the small group of (often young) businesses that are responsible for creating the bulk of U.S. jobs.

And the U.S. wasn’t alone—this decline was observed in other advanced economies of the OECD—suggesting that large global factors are at play.

This evidence runs counter to the narrative that an entrepreneurial renaissance is sweeping the globe, and the seeming endless technological change disrupting the economy. We also see plenty of those signs around us, but their impacts haven’t yet been reflected in the data. Even if they were, their effects would be following more than three decades of persistent decline.

Our most recent Brookings research suggests that slowing population growth hurts entrepreneurship. This was particularly true beginning in the 1980s in America’s West, Southwest, and Southeast regions of the United States—once places with the highest rates of new firm formation as population surged in the 1970s. During the three decades that followed, however, the formation of new businesses fell partly because population growth slowed.

In other words, population growth matters.

George Mason University Economist Tyler Cowen recently warned that the “relatively neglected field” of population economics could hold answers to the period of slow growth facing much of the developed world. For Cowen, one solution is obvious: absorb more immigrants. We couldn’t agree more.

Given the declining rate of growth of native-born Americans in the decades ahead predicted by official federal forecasters, the only other sure way to boost our work force is through more legal immigrants. Welcoming more foreign-born workers makes both economic and political sense, and in an ideal world, Congress and the President would agree on a comprehensive reform package. Since that’s not likely in the cards for now, let’s at least begin with high-skilled immigrants, who can help reverse our nation’s falling startup rate and provide a boost to our innovative capacity.

The Aging of American Businesses

This article originally appeared at Harvard Business Review

The year was 1995.

Tom Hanks was awarded an Oscar for Forrest Gump, Coolio’s “Gangsta’s Paradise” was number one on Billboard, and a young undergraduate named Monica Lewinsky began a summer internship at the White House.

Elsewhere, Timothy McVeigh murdered 168 people in Oklahoma City, three years of war in the Balkans came to an end, O.J. Simpson was acquitted of double homicide, and the World Trade Organization was formally launched on New Year’s Day.

A lot has changed since then—the iPhone, Tivo, the Toyota Prius, Google, Facebook, YouTube, human genome sequencing, GPS navigation, Skype, mobile broadband, just to name a few.

And yet, despite all of that change and memories of historic events that now seem ever distant, America’s business sector might be less dynamic than ever. That’s the major takeaway of research I co-authored with Robert Litan of the Brookings Institution and published this week. The evidence is pretty overwhelming.

Our research documents a steady rise in economic activity occurring in mature firms during the last two decades, and declining in new, young, and medium-aged firms, or what we dub “The Other Aging of America.” Mature firms (those aged 16 years or more) comprised 34 percent of U.S. businesses in 2011—up from 23 percent in 1992, for an increase of half in just under two decades.

The situation is more pronounced with employment. By our estimate, about three-quarters of private-sector employees and nearly 80 percent of total employees (private + public) work for organizations born prior to 1995. This is especially remarkable considering the volume of product innovations and household-name businesses that have emerged in the last two decades.

Further, we found that the aging of the business sector during this period has been universal across the American economy—occurring in every state and metropolitan area, in every firm size category, and in each broad industrial sector.

The evidence suggests that a decline in entrepreneurship is playing a major role; perhaps the largest. As we and others demonstrated in previous research, the rate of new firm formation has fallen by half during the last three decades, and has contributed to the decline of American “business dynamism”—the productivity-enhancing process of firm and worker churn. Fewer firm births means fewer young and medium-aged firms. It’s a matter of simple arithmetic.

Compounding this, we document a sharp uptick in early-stage firm failure rates and believe it might be playing an increasing role over time. The failure rate of firms aged one year—the youngest firms in our data outside of freshly launched ones—increased from a low of 16 percent in 1991 but rose steadily and persistently to reach 27 percent by 2011. It is possible that the increased likelihood of failure in the first year is holding back would-be entrepreneurs from forming businesses at all. In the last decade, failure rates have also increased for all firm age categories except for one—mature firms, where failure rates have held steady.

In short, fewer firms are being born, and those that are born are increasingly likely to fail very early on, as are firms that survive into young- and medium-aged years. Those that are old, on the other hand, tend to persist, allowing them to constitute a larger share of economic activity in the United States over time.

Somewhat surprisingly, we were unable to find evidence of a direct link between business consolidation and an aging firm structure. Though we do find a substantial rise in consolidation during the last few decades—confirming the widely suspected belief—it doesn’t appear to be a major contributor to business aging specifically, which has been occurring across all firm size classes, and most of all in the smallest of businesses. If business consolidation were a driving factor, we wouldn’t expect this to be the case.

This leaves some questions unanswered and some future areas for research—most notably the cause of declining business formation. But whatever the reason, our research clearly establishes that it has become increasingly advantageous to be an incumbent, particularly an entrenched one, and less advantageous to be a new and young competitor—regardless of business size, location, or broad industry group.

Life Sciences Startups: Mixed News

This article originally appeared on the MassBio blog

(with Robert Litan)

We have authored two papers recently for the Brookings Institution documenting the 30-year decline in the “startup rate,” or the percentage of firms aged less than one year as a share of all firms. Our data show this decline in the U.S. economy as a whole, in all 50 states, in all major industries, and in all but one of the country’s 366 largest metropolitan areas. We are as surprised and disappointed as many of our readers have been, as well as puzzled. How can a country that has prided itself on its entrepreneurial activities, especially over the period we have analyzed, suffered such a steady erosion in the share of its firms that are truly entrepreneurial? We don’t yet have all the answers, though we hope to begin contributing a few in several weeks.

In the meantime, we’ve been digging into the data for one of the sectors of the U.S. economy – the life sciences industry – to see if there are any more encouraging patterns. We focused on this sector, and in particular its startups, because it historically has been a driver of innovation in human health care and has played an outsized role in new job creation economy-wide.

Although we didn’t have data for life sciences going all the way back to 1980, the start date for our earlier studies, we were able to examine the industry for the two decade period, 1990-2011. The evidence, it turns out, is mixed, and can be found in our detailed study published earlier this month at Brookings. Here are some of the highlights.

First, the bad news. Overall, the life sciences industry experienced a relative 23 percent decline in startups and subsequent job creation over this period, significantly higher than the 15 percent decline across the economy as a whole.

Some more bad news. There has been significant variation across three key life sciences industries, although all were hit hard in the Great Recession. The medical devices and equipment sector saw a steady and persistent decline in entrepreneurship and net job creation, with firm formations down more than 50 percent over the period we studied. Moreover, those firms that were born created fewer jobs over time. The medical devices segment represented about one out of every two new life sciences firms in 1990, but fell to one in three two decades later – a remarkable decline that was both steep and fell from was a large base, dragging down entrepreneurship rates in the life sciences sector overall.

Here’s the good news, however. The drugs and pharmaceuticals sector has been particularly dynamic, with over 50 percent growth in new firm formation levels by 2011. Further, while the other groups (devices and labs) saw new firm formation rates fall during the 21-year period, drugs and pharmaceuticals increased by one-tenth of a percentage point. This increase admittedly is small, but against the huge drop nationwide among all types of firms, and the especially larger drop among medical device firms, we view this increase as welcome.

Finally, while the level of new research, labs, and medical testing firms grew 38 percent between 1990 and 2007, these activities were hit hard by the Great Recession. Growth contracted after 2008, and by 2011 growth was just 4 percent higher than in 1990.

The impact of this decline in number of new firms holds implications for the economy as a whole. The decline in the net job creation rate of life sciences startups overall appears to be about the same as for the rest of the economy, but despite the overall decline, the life sciences sector demonstrated a higher net job creation rate among startups relative to the rest of the private sector. In fact, life sciences startups were key drivers of job creation in the sector during the period of 1990 to 2011, whereas the effect of job creation and destruction among medium and mature firms mostly canceled each other out. The same is not the case for the private sector as a whole, where medium and mature aged firms are large net job destroyers.

The decline in new firm formations in new medical device and equipment firms in particular appears to stretch beyond the cyclical effects of the Great Recession. We haven’t figured all the reasons why, but for starters, we believe that new insurance reimbursement models, regulatory restrictions, greater competition, and venture funding scarcity have all contributed to the decline in entrepreneurship in medical devices. Policy makers and citizens pay heed.

Declining Business Dynamism: It's For Real

This originally appeared on the Brookings Institution website

(with Robert Litan)

Two weeks ago, we wrote a paper for Economic Studies at Brookings that documented the decline in business dynamism in the United States during the last few decades. We of course feel that this is an important issue, but it would be an understatement to say that we have been surprised at the level of interest our work has received.

While we’re happy to have invoked a spirited debate, we also don’t agree with some of the analysis we’ve seen of the research. We’d like to use this opportunity to respond to some of it.

What We Found

To recap, our report showed a persistent decline in the rate of new firm formations and in the job reallocation rate—a broad measure of labor market churn that results from firm formations, expansions, contractions, and failures (what we and other economists call “business dynamics”). We also showed that these declines were nearly universal across the U.S. states and metros during the 30 year period between 1978 and 2011, as well as across a broad range of industries and firm sizes.

In short, the decline in dynamism and entrepreneurship doesn’t appear to be isolated to any one segment of the economy or region, but instead has been a widely shared experience.

What we did not advance was a cause. Getting at why individuals are choosing not to launch their own companies and instead opt for employment at incumbent firms is an inherently tricky proposition. But we, and others, are making advances at getting to an answer, and hope to have some new findings to report in the future. For now, it is important to document what’s happening—the response from our report seems to confirm that.

Unfortunately, not advancing a cause also left the door open for a lot of speculation as to what is driving the decline in business dynamism—some entirely valid, some without merit in our view, and some in-between. We address in the next sections several of the more important questions or critiques.

Retail and Services

One criticism is that the decline in dynamism has a lot to do with the combined effects of (i) a shift of economic activity and employment into retail and services, and (ii) the well-known consolidation of firms in those sectors. In other words: our report simply reflected already well-known declines in firm formation and job reallocation in the sectors of the economy that have experienced the most growth. So why worry?

This critique oversimplifies. For one thing, it ignores the fact business dynamism and firm entry are both down across each of the broad industry groups, as shown in Figure A2 from our report (and reprinted here as Figure 1). Put differently, the decline we documented is not limited to retail and services.

To amplify our point, consider some additional data from the same Census Bureau series that we used in our initial report, which allow us to calculate firm entry and job reallocation rates for the retail and services sectors versus the rates for the remaining sectors as a group.

As shown below in Figure 2, the firm entry data tell two stories. First, excluding the retail and services sectors pushes the firm entry rate lower, not higher as the critique seemingly would imply. This is especially true when retail firm entrants are excluded, since the entry rate in this sector is above average throughout the three-decade period we examined. In contrast, the entry rate for services largely tracks or slightly underperforms the overall rate until around 2001, after which it increases as the non-Retail and non-Services sectors display linear declines (in fact, this decline starts in the mid-1990s).

The patterns for job reallocation rates are slightly different. As shown in Figure 3 below, the drop in the job reallocation rate (partially a function of firm entry), is significantly more pronounced for Retail relative to Services (before the late-1990s) and relative the rest of the economy prior to the early 2000’s. From there, all trends move down in a similar manner.

Services on the other hand, perform about the same as the job reallocation rate overall. The pattern in this part of the economy suggests that the decline in dynamism in Services is less driven by firm entry than is the case for other sectors.

So, we’re back largely where started and initially reported. It is true that retail and services constitute a greater share of the economy than in the past, which means any decline in dynamism in these sectors would drive down the overall rates of dynamism and firm entry disproportionately. But the evidence is more complicated. Both Retail and Services pushed up the firm entry rate, while for job reallocation, Retail pushed it down significantly while Services was about average.

In a University of Maryland working paper, economists there and from the Census Bureau took a closer look at the decline across sectors. While they make stronger comments about the decline in Retail and Services than we do, even they conclude:

“But we note that even in those sectors, we cannot account for most of the decline by taking into account simultaneously the interaction of firm age, firm size, detailed industry, geographic location and indicators of the firm operating in multiple locations. Ultimately, most of the decline in these sectors is in the “unexplained” within component.”

In other words, declining dynamism is real and the causes may be difficult to detect, but the spread of large retail chains like Walmart, Starbucks, Costco, and Walgreens does not contradict our basic finding.

High-Growth Firms

A second criticism has been that by focusing on entrepreneurship in all sectors, we aren’t separating the one’s that “matter” from those that “don’t.” In other words, by including the mom-and-pop shops (predominantly in retail and services, but also in areas like professional services and construction) along with high-growth potential firms, we are masking the true amount of entrepreneur-driven innovation occurring in the economy—the type of entrepreneurship that will lead to income growth and job creation.

While we disagree with normative judgments about which types of entrepreneurs matter and which ones don’t, there is evidence about the importance of high-growth firms. In fact, a very small percentage of firms account for the substantial majority of new jobs created in a given year.

The problem is that it is very difficult, if not impossible, to know at the time of founding whether or not firms are likely to survive and/or grow. This is true even with venture-capital backed firms, which are presumably the ones some of our critics believe that matter, but which in fact are a tiny fraction of all firms launched in any year. Conversely, research conducted at the Kauffman Foundation (where one of us used to work) has shown that the large majority of firms that do grow rapidly – making it to the Inc 500 list of fast-growing firms in any given year – never received VC money.

The key point about the entrepreneurship rate is that it represents the commercial equivalent of hockey’s “shots on goal.” The more firms started, the more rapidly growing firms are likely to emerge. For that matter, and to use another sports analogy, the more at bats we get the more doubles and triples will be produced –not just the home runs. That is a major reason why the secular decline in the new firm rate is so worrisome.

Policy and Politics

We also want to caution against those who might use or have used our findings to advance a particular partisan political agenda.

First, we have seen a number of comments in the conventional media and social media that somehow the fact that firm exits now exceed firm births, or that the decline in firm entry generally, is President Obama’s fault. We understand in this highly partisan environment, the temptation to advance such claims, but we do not believe they have merit. For one thing, it is doubtful that Presidents have much to do with the rate of firm entry. But even if they did, our data span a period of 30 years, and include periods when Presidents from both political parties have governed. And yet dynamism has continued to decline over the entire period.

Second, it is difficult to pin the blame for the secular decline in dynamism on high personal income tax rates (which matter for many startups, which increasingly are pass-through entities), either at the federal or state level. At the federal level, the top marginal tax rate has fallen since the Reagan tax cut of 1981 (the beginning year of our three decade span), and yet business dynamics have declined. Meanwhile, at the state and local levels, it is difficult to detect from the data we looked at that differences in state and local taxes have accounted for declining dynamism, since the decline has occurred in every state and virtually every metro area.

Third, we have speculated in comments since our report that mounting regulation – from all levels of government – could be one factor frustrating job reallocation while tilting against entrepreneurship. Younger, smaller firms do not have the resources that larger, more established firms do to hire full-time attorneys or compliance officers, which should put them at a progressively larger competitive disadvantage as regulations continue to grow in number and complexity. In other words, we think a more relevant conversation isn’t a generic one about regulation per se, but one that considers if our regulations systematically disadvantage entrepreneurs vis-à-vis incumbents and larger firms. We want to stress that this “cause” for declining dynamism is only a hypothesis at this stage, and awaits confirmation by future researchers, but it seems to be a plausible contributing factor.

Fourth, notwithstanding the possibility that mounting regulation in general may be one factor driving the decline in dynamism, it is also possible that the much-criticized Affordable Care Act could eventually help to begin reversing the secular decline in firm formation. This is because “guaranteed issue” of health insurance without discrimination on the basis of preexisting conditions, in principle, could loosen “job lock” that can inhibit employees with ideas for new businesses from leaving more established firms to take the entrepreneurial plunge. It will take several years, however, to see whether the data confirm or refute this plausible hypothesis. In addition, any benefits the ACA may entail in this regard say nothing about other critiques of the Act and proposals for how it may be improved.

Finally, as we noted in our initial report, the lowest hanging “fruit” for reversing the decline in startups is to increase the numbers of permanent work visas for immigrants coming here to earn advanced degrees in STEM fields and to establish businesses in the United States. Such measures would build on the well-established fact that immigrants generally are more likely to establish businesses than native-born Americans. Importing more individuals with technical knowledge, in particular, should help ensure that many of the new businesses that immigrants launch here introduce the kinds of new scientifically advanced products, services, and methods of production that are especially likely to enhance productivity growth, and thus faster growth in U.S. living standards.

With Fewer New Firms, the High-Tech Sector is Losing its Dynamism

This article originally appeared in Harvard Business Review

Believe it or not, America’s high-tech sector has become less dynamic and less entrepreneurial in the last decade. That’s the key takeaway of a recent Kauffman Foundation report I co-authored.

Despite the fanfare this vital segment of the economy and its start-ups have received in recent years, the high-tech sector is experiencing a consolidation of activity away from young firms into more mature ones, and the pace of job creation has been on a persistent decline. While it’s true that high-tech companies have been well-represented among the fastest growing firms in the past few years, the high-tech sector–like the rest of the economy–is less dynamic overall.

What do I mean by “dynamic”? The study of business dynamism involves measuring the flows of firms and workers underlying the private economy. Businesses are constantly being formed, growing, shrinking, and closing. Labor markets reflect this churning: some jobs are created while others are destroyed, and some workers move into new roles as others seek to replace them. New and superior ideas replace existing and inferior ones, while more productive firms usurp less productive ones.

A particularly important component of this dynamic process is the entrepreneur, who starts a venture to create a new market or to replace incumbents in an existing one. Entrepreneurs also play an outsized role in new job creation. While older and larger firms account for the substantial majority of employment levels, new and growing young firms drive net new job creation overall.

The process of business and labor market churning is a messy one. But it’s also fundamental to modern economies. Research has firmly established that this process of “creative destruction” fuels productivity growth, making it indispensable to our sustained economic prosperity. In other words, a more dynamic economy is a key to higher growth.

But business dynamism is breaking down.

Forthcoming research from economists at the University of Maryland and the Census Bureau shows that business dynamism has been declining across a broad range of sectors during the last few decades–and the single biggest contributor is a declining rate of entrepreneurship. A host of indicators point to a workforce that has become more risk-averse, and therefore less likely to change jobs or start a new venture.

I recently teamed up with two authors of the aforementioned research to produce the Kauffman report, John Haltiwanger of the University of Maryland, and Javier Miranda of the Census Bureau. We surveyed how these trends might apply to the high-tech sector, looking at data through 2011 and using a broader definition for high-tech that stretches beyond software and Internet companies to include things like computer hardware, life sciences, aerospace, and scientific research. What we found surprised me.

Though the high-tech sector was particularly dynamic and entrepreneurial during the 1980s and 1990s–a period when the same was not true across the economy–all that changed in the 2000s. The job creation rate (representing expanding firms) has been on a sharp decline since the beginning of the last decade, while the job destruction rate (representing contracting firms) has held about steady–squeezing net job growth in the process. By 2011, the rate of overall labor market churning in high-tech had converged with the rate for the total private sector.

Even more striking was the declining entrepreneurship. Young firms that I’ll call “start-ups”– those aged five years or less–comprised 60% of all high-tech firms in 1982. That figure fell to 38% by 2011. About half of this decline took place after the dot-com bust dissipated. The decline in both entrepreneurship levels and rates during the period associated with the Great Recession were sharper in high-tech than for the rest of the economy.

A decline in high-tech dynamism might be particularly problematic for future growth. Aside from the direct impact on productivity this sector has on technology-adopting segments of the economy, the high-tech sector itself plays an outsized role in income, employment, and productivity growthoverall. Of the job-creating young firms, high-tech start-ups are particularly dynamic–growing at twice the rate of a typical young business, and high-tech firms account for an outsized share of America’s fastest growing businesses.

How does this analysis square with talk of a “tech bubble”? One answer is that this activity, which is concentrated in web and mobile, represents only a subset of the broader high-tech sector. There’s good reason to believe that the last two years have ushered in a new wave of these typically leaner start-ups, and early-stage VC and angel investment data would back that up.

On the other hand, it may genuinely reflect slower growth across the broader high-tech sector. That appears consistent with one recent analysis that shows high-tech job growth slowing in 2013 after a rapid expansion the two years prior. Taken in the context of a longer-term decline, segmented green shoots wouldn’t reflect a robust recovery.

While this work may pose more questions than answers, the results make it clear that we must do more to promote a dynamic and entrepreneurial high-tech sector right now.

Is America’s High-Tech Jobs Machine Slowing Down?

This article originally appeared at Engine.is

Yesterday, the Bureau of Labor Statistics released its much anticipated jobs report for the month of September–more than two weeks late because of the federal government shutdown. Maybe lawmakers were trying to do us a favor because this wasn’t a great report. The unemployment rate ticked down to what is still an unacceptably high 7.2 percent, while employment grew just enough to keep up with population growth. In fact, the employment-to-population ratio remains stuck in about the same place it was nearly four years ago. These are not signals of a robust jobs recovery.

Because I’m interested in employment, economic progress, and the technology sector as a key driver of growth, I used this occasion as an opportunity to look at recent employment trends for this high-value segment of the economy. What I found surprised me.

Figure 1 shows that since peaking at an annual growth rate of 3 percent in September 2011, employment growth in the high-tech industries has steadily slowed to about 1.6 percent two years later. This matches the employment growth seen across the entire economy but falls below the rate seen for the private sector.

This trend was even more pronounced for the ICT segment of high-tech, which includes firms in computer hardware and software, information services, and Internet infrastructure (this excludes the pharmaceutical and aerospace manufacturing, and engineering and scientific R&D services industries included in the broader high-tech sector). The year-over-year ICT high-tech job growth rate eclipsed 4 percent in mid-2011, but has since fallen to 2.3 percent.

Another way to look at the high-tech workforce is by occupation–particularly because we define the high-tech industries by their concentration of workers in the STEM occupations of science, technology, engineering, and math. Since nearly 44 percent of all STEM workers are employed in the high-tech sector, that leaves millions of additional technology-oriented workers employed in other industries to look at.

In that spirit, Figure 2 shows the year-over-year percentage change in employment for the STEM occupations versus all occupations since the beginning of 2011. Because these data are noisy, I also include a data filter to establish a more visually accessible trend.

Here, we see a fairly similar trend: growth, but a slowdown in that growth. Despite a sharp uptick in recent months, the overall trend for these highly-technical high-value jobs is a clear slowing of growth, and convergence with the anemic growth rates for all occupations across the entire economy.

To get a sense of how these trends fit into other measures of economic vitality, I took a quick glance at equity price performance and venture capital investments. It’s a little bit of a mixed bag, but these measures do not contradict what the jobs data show. For example, S&P tech stock indices have slightly underperformed the broader S&P 500 index in the last two years, and after adjusting for inflation, venture capital investmentshave been flat.

Economic output data–which measure an industry’s contribution to GDP or national income–are too lagged to analyze here, but that data could help us understand whether it is the tech sector that is slowing down, or if it has been able to continue producing with fewer workers, with less investment, or at lower valuations.

While pinning-down exactly what is happening requires a more thorough analysis than is offered here, any slowdown in this segment of the economy would be problematic: the tech sector fuels innovation, its goods and services make other sectors more productive and improve the lives of consumers, and it is a critical source of national income.

I have previously documented the high-value nature of technology workers, the pervasiveness of the growth potential in this segment, and the secondary economic benefits they can bring to a region. We simply cannot afford a slowdown in our high-tech sector or its workforce–particularly as the U.S. economy continues to grind out another jobless recovery.

It’s All Relative: STEM Workers are in High Demand

This article originally appeared at Engine.is

Background

As the immigration reform debate heats up, so too has the rhetoric. One issue that has generally received broad support is the idea of expanding visas for high-skilled foreign workers—in particular those in the STEM fields of science, technology, engineering and math. Such support is based on the view that there aren’t enough qualified native-born American workers to fill demand for these roles. It also comes from the acknowledgment that employment in these fields is critical to economic growth, making them a national priority.

Despite this, some critics have voiced concerns about expanding visas for STEM workers, arguing not only that there isn’t a shortage of STEM workers, but in fact there are too many of them. Expanding high-skilled work visas, they claim, would push native-born American workers out of key technological occupations and reduce the wages of those who remain in them. Such claims are certainly outside the mainstream, but they have been taken seriously enough to appear recently in the Op-Ed page of the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, and most recently, the Atlantic.

So, which is it? Are there too few or too many STEM workers in the United States? It can’t be both. Since the truth has important implications for thousands of workers, startups, and the economy, we had better get it right.

The “we have too many high-tech workers” hypothesis is flawed because it is informed by an incomplete set of information. It also lacks common sense. The aforementioned articles rely upon a November report and a report published last week by the same think-tank, both of which point to tepid inflation-adjusted wage growth in computer and math sciences (CMS) fields—a subset of STEM—as definitive evidence of an abundance of labor supply in those professions.

The fact that inflation-adjusted wages grew slowly during the last decade lacks important context. Quite obviously, there were two economic recessions during this period—one of which was the worst contraction since the Great Depression. Both were followed by “jobless recoveries,” or prolonged periods of low employment growth after the economy has begun to grow again.

At minimum, a more relevant question is: how did wages in the CMS fields, and by extension STEM, grow relative to other professions? Looking at just one side of the story is the intellectual equivalent of concluding that the Cincinnati Reds lost last night because they only scored 2 runs. They actually won, because the team they played, the St. Louis Cardinals, scored just 1 run. Context matters.

A more complete and responsible analysis would look at relative performance as well as a broader set of measures to determine labor market “tightness”—a term that applies to areas where potential shortages may exist. A tight labor market would have some or all of these qualities relative to others: rapid employment and wage growth, low unemployment, and a high prevalence of job vacancies.

One final note before we get started: because this debate is taking place in the context of immigration reform for high-skilled workers, whenever possible the data here will be restricted to workers with at least a bachelor’s degree.

Wage Growth

Economic theory says that if shortages existed, prices (wages) would adjust upward until supply (workers) met demand (employers). But the reality is much more complicated. For example, wages adjust slowly and workers must learn new skills—especially for technical roles like in STEM. Still, it’s an important measure for assessing labor market tightness.

The chart below shows how the inflation-adjusted median wage has changed since January 2000 through 2012, for three groups of workers—those in the STEM occupations, those in the CMS subset of STEM, and those in all occupations outside of STEM.

The median wage in STEM and CMS occupations grew by an inflation-adjusted 3.5 percent and 4.0 percent respectively. That amounts to average annual growth rates of around one-third of a percent. Ouch.

But let’s take look at this in context: it’s been a very rough twelve years. As I mentioned before, there were two recessions—one of them the worst economic contraction since the Great Depression—followed by two jobless recoveries. The fact that there was wage growth at all during this period might actually be impressive.

Compared with workers in other fields, wage growth for STEM and CMS workers was actually quite robust. The inflation-adjusted median wage for all occupations outside of STEM fell by 5.5 percent during the same period, for a decline of half a percent each year on average.

Employment and Unemployment

Beyond wage growth, there are a few other measures to consider when analyzing labor market tightness—here we look at employment growth and the unemployment rate before turning to job vacancies afterward.

This chart shows employment growth since January 2000 for college-educated workers in the STEM, CMS and non-STEM categories. Employment in the non-STEM occupations increased 31.3 percent, for an average annual gain of 2.3 percent. STEM fields performed even better, growing 41.6 percent or 2.9 percent per year on average—that’s about one-third more growth than non-STEM. The CMS subset blew the others away—more than doubling non-STEM growth as it increased by 83.1 percent or 5.2 percent annually on average.

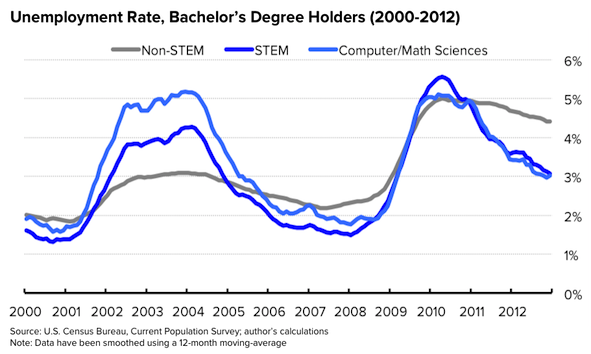

This chart shows the unemployment rate for each of our occupational groups during the same time period. The unemployment rate shows the number of people without a job, but who are willing and able to work, and are actively looking for a job (the unemployed), as a share of the total labor force (the unemployed plus the employed). In this case, the occupation assigned to an unemployed person would be the one they held in their last position.

As the chart shows, unemployment rates for college-educated workers of all varieties have been quite low over the last twelve years. The rate for STEM, and especially CMS workers, spiked during the dot-com boom—highlighting the job losses that occurred in that segment of the economy. Important to note, however, is that after peaking unemployment in STEM and CMS fell sharply. This indicates the ease with which unemployed workers in those fields were able to find new work—highlighting their relative value to employers.

The three rates peaked at about the same level during the Great Recession, though STEM and CMS unemployment has fallen sharply since mid-2010; declining by about 2.5 and 2.0 percentage points respectively during that two-year period. Unemployment for workers outside of STEM has only declined by about half a percentage point during the same period. Overall, the evidence here is more mixed: STEM workers seem to face higher volatility while unemployment for non-STEM workers rises less during recessions but also falls slower in recoveries. Even so, the STEM rate has fallen sharply in the last year.

Job Vacancies

Perhaps the most important measure for assessing labor market tightness is the ability of employers to fill open positions. If labor shortages exist, it would be difficult to fill open positions—openings would remain vacant for extended periods or discouraged employers may not even bother posting them at all. Since the reasons for not filling a job are complex, and even if they weren’t, data are elusive, the next best option is to compare the number of open positions with the number of workers available to fill them.

Here, we look at two ways of presenting that data. One caveat first—the job vacancy data used here aren’t available by level of educational attainment. Therefore, we are unable to restrict this portion of the analysis to workers with a bachelor’s degree or more. As a result, the differences here between STEM, CMS and non-STEM may be somewhat overstated.

In a market with an abundance of available labor, the ratio of unemployed per job opening would be high—a large number of workers would be competing with one another for a smaller number of jobs. Where the labor market is tight, this number would be low—in other words demand is outstripping available supply. While the reality is more complicated, this is still a very good way to estimate the relationship between demand and supply.

As the data make clear, the market in STEM and CMS fields is much, much tighter than for fields outside of STEM. At the end of 2012, there were 2.4 CMS job openings for each unemployed CMS worker and 1.4 STEM openings for each unemployed STEM worker. That’s a lot of job openings for each unemployed worker to potentially be matched with. The exact opposite was true in non-STEM fields, where 4 unemployed workers battled for each job opening.

If you’re unconvinced that unemployed workers are an adequate measure of available labor, we can extend that definition to include workers who are currently employed in those roles. Recall that the unemployed plus the employed constitute the labor force. Here, we use the labor force as a measure of labor availability for STEM, CMS and non-STEM workers.

This time, the number of job openings is in the numerator and is expressed as a share of the labor force. This is often referred to as the job vacancy rate. Here, a bigger number would indicate a tighter labor market, showing that there are a larger number of job openings relative to the ability of the labor force to fill them. A smaller job vacancy rate would indicate the opposite.

We still see a similar story, though less pronounced: there is a larger number of job openings relative to available labor to fill those roles in STEM and CMS, compared with fields outside of STEM. The difference between this chart and the prior one likely has to do with a more rapidly declining unemployment rate and higher employment growth in STEM and CMS—both positive signs.

Conclusion

Wage growth for STEM and CMS workers with at least a bachelor’s degree has been more robust during the last twelve years than it has been for workers outside of these fields. Not only did wages grow at the median for these fields while wages in all other professions fell substantially, that growth also reached workers with a broader set of income levels.

Looking at other measures, available labor to meet job openings has been scarcer for the STEM and CMS fields, employment growth has been more robust, and unemployment has fallen to lower levels. The evidence is more mixed when it comes to unemployment, but overall the consistency across measures and the magnitude of differences point to tighter labor markets in these fields.

In fact, according to performance thresholds to assess labor market tightness outlined in a comprehensive review of the literature published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the CMS labor market is tight on each of three metrics (employment, wages, and unemployment). STEM is tight on two of three (wages and unemployment) and goes halfway on the third (employment). The BLS report doesn’t provide threshold criteria for job vacancies because these data weren’t available at that time.

This highlights a few important points worth making. Firstly, providing definitive evidence of the existence or nonexistence of a labor shortage in any profession is difficult, both because what constitutes a shortage can be broad based and because the appropriate data can be elusive. It’s irresponsible for researchers to claim there is an oversupply of STEM workers because of one metric taken outside of its proper context.

To be clear, the approach here does not claim that there is a shortage of workers in STEM and CMS fields. Instead, it shows that these labor markets are tighter than others based on a broad set of measures. At minimum, it is a clear rejection of the notion that we have too many high-tech workers in the United States—an argument that not only fails on evidence, but common sense as well.

Secondly, and perhaps most importantly, the argument about whether there is or is not a true shortage of STEM workers misses the entire point. Recent research has shown that foreign-born STEM workers increase employment and wage opportunities for high-skilled native-born American workers (STEM and non-STEM). In other words, these workers are complementary to, not substitutes for, one another. Foreign-born STEM workers are important contributors to productivity gains, which fuel economic growth and national prosperity. And because these workers tend to be employed in sectors of the economy that compete globally, if the United States doesn’t capture the talent and therefore growth, someone else will.

Let’s get our facts straight, and in context, as we move forward with immigration reform. Sure, foreign worker programs like the H-1B visa have a number of problems and need rethinking. So does our education system. But let’s fix those, not shut our doors to high-skilled foreign workers based on poor economics. That would be throwing the baby out with the bathwater, and in the process, shooting ourselves in the foot.

California Tax Change Will Hurt Entrepreneurs and Job Creation

This article originally appeared at Engine.is

In December, the California Franchise Tax Board (FTB) announced changes to capital gains tax exclusions on Qualified Small Business (QSB) stock holdings. The change stemmed from an appellate court ruling that found minimum in-state asset and employment requirements during the holding period of the QSB stock unlawful under the U.S. Commerce Clause. Rather than remove the in-state asset and employment threshold requirements, the FTB instead chose throw the baby out with the bathwater and eliminate the capital gains tax exclusions altogether—effectively increasing state taxes on investments held in QSBs from 4.65 percent (under a 50 percent exclusion) to 9.3 percent (under zero exclusion).

The real attention grabber has been the FTB’s choice to make the change retroactive to 2008—with penalties and interest—despite the fact that investors were following what was then current law. While investors are up in arms over this, entrepreneurs may actually have the most to lose moving forward.

Capital is the lifeblood of startups. This move by the FTB, which amounts to a tax hike for investors, will likely make capital scarcer for young businesses. Fewer startups means less job growth; for the last 30 years, young companies have provided all of the net new job creation in California and the United States as a whole.

Matching an existing framework with data on California, it’s possible to generate a conservative, back-of-the envelope, estimate of investment startups in the state might lose. This drop would likely have a negative impact on the California economy—not only have startups been the engine of new job creation in the state, but the QSB capital gains tax exclusions were targeted especially at businesses with the highest growth potential.

Estimating Investment Impact of Tax Change

A 2012 Kauffman Foundation report provides the framework for estimating the impact of tax changes on early-stage investments in startups. The report yields a conservative estimate of the additional investment in startups that would occur if 100 percent of the capital gains held at least five years were excludable from federal taxation, compared with an earlier exclusion of 50 percent. In other words, the report tells us how much investments of this nature might increase when taxes are reduced.

We employ that same framework here but move in the opposite direction, answering the question: how much would investments in startups decline from what amounts to a tax increase? Then we apply this estimate to data on investments in California startups.

Let’s unpack the potential investment response to the tax increase by using a hypothetical example. The Kauffman report states that a reasonable assumption for a real pre-tax return on privately held investments in startups in the current interest rate environment is 10 percent. At least one prominent angel investor group agrees, and so do we.

Under this assumption, an investment of $100 would be worth $161 after five years on a pre-tax basis. If the tax rate were 4.65 percent, as it was under the previous 50 percent exclusion in California, that same investment would be worth $158, for an average annual return of 9.6 percent. Under a 9.3 percent tax rate regime (zero exclusion), that same investment would be worth $155—returning 9.2 percent per year on average. Capital gains in QSBs are currently fully excludable from federal income taxes and were in 2011 as well—the base year used in our analysis.

A change in the effective tax from 4.65 to 9.3 percent results in a 4 percent drop in the average annual return on the investment (from 9.6 percent to 9.2 percent). Based on previous research on the topic, and conversations with experts in the field, the Kauffman report concluded that the responsiveness (the “elasticity”) of such a change in the rate of return on aggregate investments is a conservative 0.5—or half the change in return. In other words, the 4 percent decline in a typical return would result in a 2 percent drop in investment overall. Two percent may not seem like a big decrease, but when applied to a large base like in California, it can be.

To see how big of a dent 2 percent could make, the baseline estimate of equity invested in California startups is tabulated from three sources of “seed funding”:

In total, an estimated $4.1-6.1 billion was invested in California seed-stage startups in 2011. It is reasonable to assume that essentially all of these seed funds were invested in traditional C corporations—the type of company that is most suitable for startups and is eligible for the QSB tax deduction. For scope, that amounts to between 32 and 47 percent of such investments in the entire United States.

With a baseline of $4.1-6.1 billion, and a 2 percent reduction in investments from the tax change, we’re left with a decline of $85-127 million in investment in startups each year in California. Now, $85-127 million per year may not sound like a whole lot of money relative to total investments in startups broadly, but over ten years it totals between $853 million and $1.27 billion. Moreover, whether we are talking about an annual or decade-long framework, considering that seed-stage companies may receive as little as $15,000 in funding (though a typical amount is in the hundreds of thousands), we’re talking about a lot of companies that may be adversely affected.

What’s more, this is almost certainly an underestimate of the value of investments in California startups and the effect the tax change would have. To begin, the Kauffman report reiterates that its framework is likely to yield conservative estimates. Most notably, it states that the elasticity estimate of 0.5 is likely conservative—meaning that for each 1 percent decline in a typical rate of return, overall investments would fall by more than 0.5 percent.

Secondly, since QSB status in California applies to companies with up to $50 million in assets, many businesses beyond the “seed/startup stage” would qualify. As a result, we are surely undercounting the pool of investment in the state that would be affected by the tax change.

Third, the 2011 statutory state tax rate applied here (9.3 percent) is lower than the marginal rate charged to those with incomes above $1M (10.3 percent), which would apply to a non-trivial number of investors in startups. These investors would be adversely affected even more than our rough estimates indicate.

Finally, the Kauffman framework was previously applied to federal tax—which would be applied uniformly across states. Holding federal tax rates and all other factors constant, other states would have an advantage against California. According to the Angel Capital Association, twenty states have tax incentives for angel investors and California isn’t one of them. For example, states like Wisconsin are actively partnering with investors to increase investments in startups.

In addition to all of this, Proposition 30, which was adopted by California voters in November, raises state income taxes to varying degrees on individuals who earn more than $250,000 per year. Though this is outside the scope of our analysis—both because the year studied pre-dates that particular tax hike and because arguing the merits of state tax policy broadly goes beyond what we’d like to accomplish here—it will further compound the issue, potentially leading to even more declines in investments in California startups.

Economic Impact

Though data are not readily available to directly tie investments in QSB-type businesses specifically to the economic impact in California, data from the Census Bureau can illustrate the important role that new businesses play in job creation in the state.

Between 1980 and 2010, businesses in their first year added an average of 398,193 new jobs each year. Companies aged one year or more, as a group, subtracted an average of 192,501 each year during that same period. This occurred because the forces of job destruction (through business contractions and closures) were stronger than the forces of job creation (through firm births and expansions) for businesses older than a year old as a group. In other words, outside of startups, net job creation in California was negative during the past three decades.

In addition to the job creation dynamics of new firms, among existing businesses it is young firms (those less than five years old) that have the biggest effect on job creation. Taken together with the chart above, we can say that new and young firms are responsible for all net new job creation during the past few decades.

Conclusion

The FTB’s tax change is likely to reduce investments in California’s startups by a conservative 2 percent each year, translating to $85-$127 million fewer investments annually based on 2011 data. This can’t be a good thing for the economy or job creation in the state. At a time when the state unemployment rate hovers around 10 percent, California can hardly afford to place any of its companies at a competitive disadvantage—especially not those poised for high growth. On top of that, a recent survey of small businesses sponsored by the Kauffman Foundation found California to be among the least friendly for entrepreneurs.

Though it is understandable that state authorities are searching for ways to improve the fiscal situation of California, this isn’t a good way to go about it. The entire point of providing a tax incentive for these investments is to make them more attractive to investors, relative to others, precisely because seed-stage investments are very risky and because startups have important spillovers to the economy—namely that they fuel economic growth and job creation.

Moving forward, not only should state policymakers reinstate the QSB capital gains exclusion, they should extend it—making capital gains on these investments fully excludable. There is already precedent for this at the federal level too: in 2010 Congress temporarily made these investments fully excludable and recently extended this policy through 2013. If Washington can see the wisdom in doing this, why can’t Sacramento?

Debunking the Myth of the Startup Hub

This article originally appeared in The Wall Street Journal

A common misconception in the United States is that high-tech firms exist only in a few cities that coalesce around the coasts. The reality couldn’t be further from the truth. Yes, it’s true that places like Boston, Seattle, San Francisco and Silicon Valley are important hubs of high-tech activity, but so are places like Boulder, Colorado, Huntsville, Alabama and Wichita, Kansas.

The Bay Area Council Economic Institute published a report in December that details recent trends of high-tech employment and wages throughout the United States. The report found not only that high-tech jobs are a critical source of employment and income in the U.S. economy, but also that growth in the high-tech sector has been increasingly occurring in regions that are geographically and economically diverse.

As evidence of this, one of the report’s findings was that a statistically significant relationship could not be established between the concentration of high-tech jobs in a region and whether employment in the high-tech sector had grown in the last half-decade or the last year. In other words, high-tech jobs have been growing outside of the well-known tech hubs.

Regions should want high-tech firms in their communities because they pack a lot of economic punch. This can be illustrated by the multiplier effect, whereby the creation of one high-tech job in a region creates an additional 4.3 jobs in the local services economy of the same region in the long run. Compare that with the manufacturing sector, long a darling of regional development authorities. It has a local multiplier of 1.4. Although this is quite large, it is still just one-third the size of the local multiplier stemming from high-tech.

So, what does all of this have to do with startups? The short answer is that high-tech firms are an important source of entrepreneurship in the U.S. economy. While this probably isn’t a controversial statement for most, the actual magnitude of the high-tech sector’s share and distribution of startups remains largely unmeasured. This is a topic my colleagues and I are currently researching and intend to publish in a companion report to Technology Works within the next few months.

For now, let me provide a few data points from our preliminary analysis. Though high-tech businesses existed in 98 percent of U.S. counties in 2010, new high-tech companies were born in 62 percent of counties during the same year. What is more, high-tech startup growth is occurring in regions outside of the traditional tech hubs. For example, 70 high-tech startups were formed in Fort Collins, Colorado in 2010, while 88 were started in Baton Rouge, Louisiana and 162 in Columbus, Ohio. All marked increases in excess of 60 percent over the year. A total of 117 major metros increased high-tech startups by at least 20 percent in 2010 from the year prior, and 50 did so compared with five years earlier.

This analysis of the high-tech sector will help inform how business formation and job creation patterns for innovative and growth-oriented “startups” differ from those for “new businesses” generally. As innovation pioneer Paul Graham noted, startups have fundamentally different business goals and should not be lumped together with new businesses broadly. Research by economists at the University of Chicago backs this assertion, finding that three-quarters of nascent entrepreneurs have no intention of innovating or growing substantially.

Differentiating potentially high-growth startups from other new businesses is important for public policy too. Ronnie Chatterji, a Duke University business school professor and former Obama White House adviser, points out that potentially high-growth firms like those in the high-tech sector command an entirely different set of policy priorities. According to Engine Advocacy, a non-profit that connects startups with policymakers, reform is required in areas like education, immigration, intellectual property, and financial regulation. State policymakers can create investment-friendly environments through tax incentives and regulatory reform.

To summarize, high-tech jobs are important to the economy and are growing in a wide and diverse set of regions. The same is true of high-tech startups. The issue of whether high-tech startups are able to survive outside of well-established tech hubs is one of many important questions that we are currently working to answer in our research. We hope to have that answer to you shortly. Stay tuned.